|

November

3, 2010 November

3, 2010

Geneva Centre International Symposium

on Autism

The logo and the text below are copied and pasted from the

Geneva Centre For Autism website at

www.autism.net

Imagine living in a world where you are constantly bombarded with

messages that you don’t understand, where you can’t find the words to

express yourself and where you continually feel a sense of loneliness

and isolation. This is the reality that many children with an Autism

Spectrum Disorder (ASD) face every day.

At Geneva Centre for Autism, our services build skills in children so

they can realize their potential. Working in partnership with the

Ministry of Children and Youth Services and other community partners, we

develop and deliver a wide range of innovative services that meet the

unique needs of children on the Autism spectrum. These services are

provided by a multi-disciplinary team that includes psychologists,

speech language pathologists, occupational therapists and behavioural

therapists.

HOW TO GET STARTED The point of entry to access Geneva Centre for

Autism's services is done by calling the Centre at 416 322 7877. Your

call will be directed to the appropriate department.

Ron was

referred to the Geneva Centre For Autism by the Hospital for Sick

Children right after he was diagnosed with autism Asperger Syndrome and

from thereon started his journey into the world of autism. It was the

Sick Kids hospital's Children Development Centre (CDC) who referred Ron

to the Geneva Centre for Autism. With their wide array of experience,

their involvement has placed Ron's developmental needs in perspective

and context. (Notes from Ron's parents)

The Geneva Centre Asperger

Program is designed to meet the specific needs of individuals with

Asperger Syndrome between the ages of 12 and 18 years and their

families. The program comprises the following elements:

®Individualized

consultation with members of a multidisciplinary team including:

lSpeech and Language Pathologists lOccupational Therapists lBehaviour/Communication Consultants lDevelopmental Paediatrician lBehavioural Psychologist

®Series Workshops:

Parent training on topics including behaviour, social communication and

independent daily living.

®Groups: Teen groups

focusing on learning social boundaries, building self-esteem and coping

with anger and anxiety.

The Geneva Centre

provided Ron with workshop for us and Ron's caregiver with behavioural

intervention therapy and skill building workshops using music and social

skills teaching strategies., Ron with his caregiver attended workshops

to learn group skills through music, role-playing, and performance. Ron

and his parents were introduced to, and explored the use of a variety of

musical instruments to learn, take turns, and to share experiences and

enjoyment with others. All these were facilitated by a Music Therapist,

a Social Skill-Building Group Facilitator, and supported by a volunteer.

To register your child for TPAS services, please call Surrey Place

Centre's intake at 416 925 5141 ext. 2289 or speak with the intake

worker at Geneva Centre for Autism at 416 322 7877.

Visit the

Geneva Centre Website

(Click arrow BACK in browser to return here)

STORY FEATURED IN GLAMOUR

MAGAZINE They're

Autistic—and They're in Love

BY LYNN HARRIS

FEBRUARY 1, 2009 7:00 PM

lindsey nebeker & dave

hamrick

There are two bedrooms in the cozy Jackson, Mississippi, apartment: Dave

Hamrick's is like a dad's den, with a striped beige armchair and a

hanging map; Lindsey Nebeker's is darkly girly, with spiky dried roses

hung over a bed topped by a graphic leaf-print quilt. After work on any

given evening,

Dave and Lindsey are

likely to be orbiting the home separately, doing their own thing. Dave

may be flipping through magazines, pausing to stare fixedly at design

details or leaning in to inhale the scent of the pages. Lindsey

typically sits down to eat alone—from a particular plate with a

particular napkin placed just so—and may slip so deeply into her own

world that Dave has learned to whisper "Psst…" when he approaches so as

to not startle her and, on a bad night, make her scream.

An observer might

assume the two are amicable, if oddball, roommates. But Lindsey, 27, and

Dave, 29, are deeply in love. And they are autistic.

Every day of their

relationship, these two beat tremendous odds. That's because the very

definition of autism suggests that for adults with this disorder,

love—especially the lasting, live-in kind like Lindsey and Dave's—is not

in the cards at all.

About 1.5 million

people in the United States (an estimated one fifth of them are female)

have autism, with varying degrees of severity. The disorder can create

sensory issues, like hypersensitivity to touch and sound, and impair

social skills. While some autistics are gifted (often in music or math),

they may be utterly baffled by the nuances of small talk and eye

contact. Expressing empathy can be virtually impossible. Imagine a first

date—never a breeze for any of us—with those limitations.

"I hear a lot of

loneliness, sadness and fear among the autistic adults I meet," says

Stephen Shore, author of Beyond the Wall and an internationally

recognized expert on autism who has the disorder himself. "Without a

natural understanding of communication, it's much more difficult for

people with autism to find and sustain an intimate relationship." They

have hearts that feel; it's the funky wiring in their brains that makes

things so challenging.

Contrary to

stereotype—the Rain Manesque loner who'd rather count toothpicks than

make friends—adult autistics often know what they're missing out on and

hope to find love, like anyone else. Since hanging in a crowded bar or

going on a blind date can be terrifying, many connect through

social-networking websites. Still, successful relationships aren't very

common, especially relationships in which both partners have autism.

Lindsey and Dave have

experienced their fair share of heartache: at school, among so-called

friends, in their search for partners. Yet both have also summoned the

courage to take a risk, perhaps the biggest risk of their lives, for

each other. Theirs is a still-unfolding tale—an unconventional story

about unconditional love.

Autism has been making

headlines lately, especially now that more and more children are being

diagnosed with it. Celeb mom Jenny McCarthy, for one, speaks and writes

about her son's autism.

The head writer for

Days of Our Lives developed a story line about an autistic child based

on her parental experience. Last fall, autism-awareness advocates raised

hell over the "Autism Shmautism" chapter in comic Denis Leary's latest

book.

Observations included "Yer

kid is not autistic. He's just stupid. Or lazy. Or both."

The attention, good and

bad, has made it somewhat easier for adult autistics to find acceptance

in the world. Former America's Next Top Model contestant Heather Kuzmich—who

has Asperger's syndrome (considered an autism spectrum disorder) and who

had trouble making eye contact in TV interviews—has become a role model.

Claire Danes is starring in a forthcoming HBO biopic about best-selling

autistic author Temple Grandin. Also helpful are sites like

wrongplanet.net, geared toward autistic adults, where users can find

answers to questions such as "How do I learn to flirt?"

Lindsey, an

auburn-haired beauty with an artistic, bejeweled style you might call

peasant-goth, has been more fortunate than others (including her

severely autistic younger brother).

When she was 19 months

old and not talking, her parents tested her for autism, and she got the

benefit of early treatment. Today, her occasional wandering gaze and the

forced cheer in her voice make her seem just a bit off. It takes effort,

she says, not to sound "robotic."

Even as Lindsey's

speech caught up and her talent for playing piano emerged, she developed

habits typical of autistics: staring for hours at the fibers of a

carpet, for example, or performing soothing rituals like stepping on

cracks in the sidewalk.

Classmates teased her

mercilessly, and she'd come home with kick me signs on her back. Real

friendship seemed painfully out of reach for the eccentric, awkward girl

who came across as blunt. In high school, when another student asked

Lindsey what she thought of her new makeup, Lindsey recalls, "I told her

it looked fake. She became silent, and I knew I had blown it."

Depressed, Lindsey burned herself with a curling iron and cut her arms

with safety pins, hiding her injuries with sweatshirts. "Lindsey's

struggles were heartbreaking," says her mother, Anne Nebeker, 63, a

retired teacher in Logan, Utah. "I was very anxious about how she would

manage as an adult and whether she would have a social life at all or

find love."

Yet Lindsey's torment

fueled a determination to learn the very skills that eluded her. Her

best resource: Dale Carnegie's self-help classic How to Win Friends and

Influence People.

Advice as simple as "Be

a good listener" began to help, especially by college. The subtleties of

romance, however, remained a mystery. She'd fool around with a guy and

get dumped a few days or weeks later without explanation. "I had no idea

what I was doing that was scaring guys away," says Lindsey. "I felt like

I had failed somehow." In her early twenties, she gave up. "I decided to

focus on the friendships I'd managed to make," she continues, "and quit

worrying about love altogether."

LINDSEY MET DAVE

That's when she met

Dave. It was 2005, and they were at an autism conference in Nashville.

Diagnosed at three, Dave grew up with pronounced fixations. He'd tote

around empty Clorox bottles, and carry a thermometer to assess the air

temperature. Like Lindsey, he had trouble making friends.

Dave also has

Tourette's syndrome, which can overlap with autism; it's the cause of

his near-constant head jerks and occasional stuttering and grunting

noises. His parents were told he would always be in special education,

never able to work or live on his own. By fourth grade, he was in a

mainstream class; he went on to college, where he majored in

meteorology.

When he and Lindsey met, Dave says, "I was hopeful, but realistic." They

e-mailed and talked on the phone, then hung out again a few months later

at a conference in Virginia. On their last night there, at a café, Dave

took the plunge. Seeing Lindsey's hands resting on the table, Dave

reached for them. "When she didn't pull away, I knew I had a positive

result," he says in his endearingly geeky, textbookish way.

The next day, he gave

her a bouquet. "I'd never gotten flowers from anyone, other than my dad

after a piano recital," says Lindsey. Looking Dave in the eye was hard

for her. So, she says, "it was a relief to close my eyes and lean in to

kiss him. I had my guard up, but some part of me was willing to give it

a try."

Two years later,

Lindsey and Dave moved in together. It's a big step for any couple, but

for autistics, it can mean merging two rigid ways of life. Dave likes it

cool; Lindsey likes it warm.

Dave needs his mattress

firm; Lindsey needs hers soft. These may sound like trifles, but what's

merely irritating to others may be, for an autistic, 20 fingernails on

20 blackboards. They've discussed every last detail, down to lightbulb

preference.

When Dave awakes for

work, Lindsey—a night owl—may still be up from the evening before. By

noon, she's improvised a few riffs on her beloved Steinway and is

performing the 20-minute ritual of preparing her three thermoses of

coffee (touch of flavored syrup, drop of almond milk, heat, adjust,

repeat), which she will take with her to her job…at Starbucks.

Being a barista isn't

her Plan A. She dreams of studying photography or special ed in grad

school. Dave has turned his fixation on temperature into a meteorology

career (his e-mail name is "weatheringautism").

An entry-level

forecaster at the National Weather Service, he finds his job exciting.

It requires only limited face-to-face contact with strangers; on a

typical day, he gives callers weather reports or heads out, alone, to

release a weather balloon.

Both often come home

exhausted, like actors who've been on stage all day. That's one reason

Lindsey and Dave need so much time alone after work, and why they rarely

call each other to check in and chat. "Every day, we put out so much

effort to speak properly in the workplace and other social settings,"

says Lindsey. "When we talk on the telephone, our conversations normally

don't last long because we get uneasy when the small-talk script runs

out."

On weekends, they're

more likely to prowl a bookstore than go to a party or a restaurant.

Their friends—mostly from college and conferences, some of whom are

autistic—don't live nearby. They also prefer to eat by themselves. Dave,

as if he had superhero hearing, is sensitive to the sound of chewing. He

can eat only cooked vegetables—never raw, crunchy ones. Lindsey finds it

so torturous to deviate from her food rituals that Dave's occasional

invitation to dine out can send her into sobs. "I just keep telling him,

I'm so sorry, I can't,'" she says. "I feel awful about it."

Once in a while, with

enough notice, Lindsey says yes and they'll head to a bright and

bustling pan-Asian buffet; it's the opposite of romantic. Dave, lit up

like a kid on Christmas Day, will happily put away several crabs' worth

of crab legs. Lindsey, wary of food she didn't prepare herself, would

rather prod stiffly at her wasabi than moon over Dave. But what other

diners can't see is something even more tender than canoodling: Lindsey

and Dave's willingness to step outside their comfort zones to please

each other.

ADJUSTING TO SEX

Adjusting to sex took

time. Lindsey was somewhat nervous about the fact that she was a virgin

and Dave was not. "Spontaneity was not an option," she says. "People

with autism really have to mentally prepare for everything." She felt

bogged down by the procedures she'd established in her head from seeing

romantic movies like Pretty Woman—"OK, now I'm supposed to take off his

shirt." Three years into their relationship, though, they readily visit

each other's beds.

Marriage, they say, is

a possibility; children, they're less sure about. Both worry about a

genetic predisposition to autism, a valid concern, especially given that

both Lindsey and her brother have the disorder. Even if they adopt,

parenting seems perilous. "Dealing with our rituals and sensory issues

demands so much from us," says Lindsey, "that I don't know how we'd take

care of someone else."

Lindsey still gets

depressed when people misunderstand her. "Sometimes, after a bad

experience, I shut myself off from the rest of the world," she says. "I

don't have to face judgment in my room." Recently, as a man at work was

talking, she tuned out but kept nodding and smiling (a frequent habit).

Suddenly he blurted, "Did you hear what I said? I got mugged last

night." Lindsey was crushed. "It's exhausting," she says, "to be 27 and

still have to work at getting interactions with people right."

These are the times

when she needs Dave most. "He reminds me that tomorrow is another day,"

she says. "He makes me feel like I'm worth something." Dave loves to

stand behind her, wrap his arms around her waist, press his nose into

her hair and take long, deep breaths. Last Valentine's Day, he festooned

their bathroom mirror with plastic gel hearts (he's been obsessed with

the shape since he was a kid). They're still there today.

Though connecting with

others will be a lifelong struggle, Lindsey and Dave have formed a bond

that defies their autism. They may sometimes come across as blunt to

strangers, but speaking their own minds clearly and directly—just as

they did when they moved in together—has helped their relationship.

There's none of the "if you have to even ask what's wrong, then forget

it" passive-aggressiveness many couples experience, no expectation of

mind reading. "People like Lindsey and Dave put so much thought and

dedication into making their relationship work," says Diane Twachtman-Cullen,

Ph.D., a speech-language expert who specializes in autism and knows the

couple well. "Frankly, we could all take a page from their playbook."

Lindsey's mom is

similarly awed. Anne Nebeker recalls that when Lindsey and Dave came to

visit her for the first time, "we went to a local lake. The two of them

were running around and splashing water at each other, and I was so

pleasantly surprised to see them doing a normal-couple thing like that.

Even when Lindsey calls

him Hon' and it sounds natural, not forced and rehearsed, I am amazed. I

am so happy to see her in love."

These days, when

Dave whispers as he approaches Lindsey, she'll whisper back; it's become

a term of endearment. "Psst…," he'll say after he walks in the door and

sees Lindsey in the living room. Her face lights up when their eyes

meet. "Psst!" she'll respond, smiling. She knows that with Dave, she's

in a safe place. "I'm so lucky to have found him," she says. "When I'm

with him, I forget about my challenges."

Writer Lynn Harris is a

contributing editor at Glamour.

PHOTOS: PHOTO: COURTESY OF GORDEN NEBEKER

CLICK IMAGE TO LEARN MORE...

Geneva Centre 2010 International Symposium

on Autism

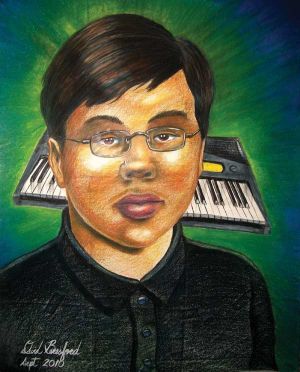

Ron

Michael Adea - 2010 Symposium Ambassador Ron

Michael Adea - 2010 Symposium Ambassador

At each International Symposium on Autism, Geneva Centre for Autism

provides a poster featuring an individual with autism who has

demonstrated an outstanding creative talent of his or her own as our

Symposium Ambassador. Previous Geneva Centre for Autism “Ambassadors”

have included remarkable painters, sculptures, cartoonists and even

dancers.

POSTER ARTIST: David Beresford

Source:

http://www.autism.net/symposium-ambassador2010.html

Adults with Autism

What happens when

someone with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) leaves school and makes the

transition to adult services, college, work, job training, or a new

living situation?

Coming of Age:

Autism and the Transition to Adulthood

Marina Sarris

Interactive Autism Network at Kennedy Krieger Institute

ian@kennedykrieger.org

Date Published:

April 8, 2014

What do we mean by the

transition?

When you get to be 18 or 21, it's like falling off a cliff. We don't do

a great job of educating parents about what's going to happen after

school ends.

Technically, the transition is a formal process that begins by age 16

for a student who receives U.S. special education services. That is when

school systems must begin helping those students plan for life after

high school, such as college, work, vocational training, independent

living and adult disability services.

Autistic and seeking a place in an adult world

Teachers will ask students about their interests and develop goals to be

inserted in the student's Individualized Education Program (IEP). Adult

service agencies may be invited to participate, since they may be

handling the student's needs after he leaves high school or reaches age

21.

But don't assume a young adult is merely transferring between two equal

disability systems, one for children and one for adults. The adult

system is different at its core.

A student with a

disability who is eligible for U.S. special education services is

guaranteed to receive them until he graduates high school or turns 21.

Not so with adult services. That same student may be eligible for adult

services, such as housing assistance, day programs, supported employment

and job training. But whether and when he receives those services

depends on funding. States often administer such programs through

developmental disability and vocational rehabilitation agencies. The

states set their own guidelines for eligibility and funding.

Many states have waiting

lists for adult services, particularly housing. For example, Connecticut

had 15,000 people with intellectual disability who were eligible for

services in 2013, but only limited funding.

To receive funding,

someone on a waiting list had to be in a crisis, such as facing

homelessness, abuse or a progressive illness. Many states parcel out

funds for adult services to those who are in crisis or have the most

severe needs.

"When you get to be 18 or 21, it's like falling off a cliff," said Zosia

Zaks, a Certified Rehabilitation Counselor who works with adults with

ASD. "We don't do a great job of educating parents about what's going to

happen after school ends."

The responsibility for

obtaining services also shifts. Public schools are tasked with finding

children with disabilities and providing them services. But in the adult

system, you must apply for services and ask for what you need. "It

requires self-advocacy," explained Mr. Zaks, program supervisor at the

Hussman Center for Adults with Autism in Towson, Md.

Youth with Autism

at Risk After High School

The National Autism Strategy aims to help all adults with autism

into work. Kellie Nauls, project coordinator for the Moving On

Employment Project in the Shetland Islands, talks about how a pilot in

the region is helping young people with autism to find and keep a job.

CLICK IMAGE TO LEARN MORE...

Once in college, students with disabilities will have to request the

accommodations they need to be successful, and their schools need only

provide the "reasonable" ones. Parents who consider themselves experts

on their child's special needs may find themselves largely shut out of

the process after high school because of privacy laws.

Students who have

experience making their needs known will fare better in this

self-advocacy system.

Not surprisingly, the road to adulthood can be rocky. More than half of

the youth with ASD had no job and no involvement with postsecondary

education in the two years after leaving high school, according to a

study in the journal Pediatrics.

"It appears that youth with an ASD are uniquely at high risk for a

period of struggling to find ways to participate in work and school

after leaving high school," according to the research team, led by Paul

T. Shattuck Ph.D. They also warned of "potential gaps in transition

planning" for youth with ASD,3 a caution mentioned by other researchers

studying the post-high school employment of people with autism.4

But don't panic. There are

things parents, teachers and schools can do to help with the transition.

Start Transition Planning Early

Parents ask me, 'When should I start with transition planning?' I say,

'Age six,' and people look at me like I'm out of my mind. Ernst

VanBergeijk Ph.D.

For one, you can begin planning sooner. Experts say that transition

planning ideally begins when children are very young, as parents and

schools lay the foundation for skills needed to negotiate adult life.

"Parents ask me, 'When should I start with transition planning?,'" said

Ernst O. VanBergeijk, Ph.D., M.S.W., associate dean and executive

director of the Vocational Independence Program at New York Institute of

Technology. "I say, 'Age six,' and people look at me like I'm out of my

mind. 'That's way too early,' they say. But I say, you need to visualize

your child at age 21. What are the building blocks for independent

living skills?"

What is it like to be an independent adult?

Daily living skills – which include personal hygiene, housekeeping and

handling money – can be taught beginning in early childhood, he said.

Complex skills can be broken into small steps and gradually increased in

complexity as a child gets older and learns to do each step, he said.

Take work and money management skills, for example. A parent can begin

by teaching her child to perform simple chores and giving him an

allowance for the work, he said. The child can learn about money by

placing his coins into separate tins for spending and saving.

The payoff for learning these skills is high. A 2014 study of adults

with ASD found that those with better daily living skills were more

independent in their job and educational activities.5

Focusing on Daily Living Skills in the Transition Years

Schools may not always consider daily living skills when drafting

transition goals for a diploma-bound student. Parents can request that

those skills be included in the IEP, said Dr. Amie W. Duncan, a

psychologist who has studied this issue. Her research team found that

half of the students with ASD and average or above average intelligence

had deficits in daily living skills.6

Another item to consider: adding "travel training" as a transition goal.

Travel training is hands-on teaching about how to travel safely to jobs

and other destinations using public transportation.

Some programs, such as Project SEARCH, help move students with

disabilities into workplaces during the transition years.

Daily Living Skills: A Key to Independence for People with

Autism

Marina Sarris

Interactive Autism Network at Kennedy Krieger Institute

ian@kennedykrieger.org

Date Published:

April 10, 2014

Cafe Serves Up Jobs For Young Adults With Autism

With a broken alarm clock, Zosia Zaks feared oversleeping for an 8:30

a.m. college class. Who wouldn't? But his solution was anything but

typical; he decided to sleep in his classroom to make sure he wasn't

late.

As someone with

Asperger's Syndrome, he lacked a so-called adaptive skill – in this

case, performing the steps needed to replace a clock battery – that

makes adult life easier.

Mr. Zaks, now a Certified Rehabilitation Counselor, and other experts

say adaptive skills, or skills of daily living, need to be taught

explicitly to people on the autism spectrum. Taking a shower, brushing

your teeth, riding a bus, crossing the street, shopping or preparing a

meal: all of these are adaptive skills.

Such skills are considered essential to adulthood. "For example,

difficulties with everyday activities such as bathing, cooking,

cleaning, and handling money could drastically reduce an individual's

chance of achieving independence in adulthood," according to

researchers.1

Sometimes, parents and teachers of children with autism may focus more

attention on teaching academic and behavior management skills than on

daily living skills. Some may assume that daily living skills are less

important. Or they may believe that a person with average intelligence

will learn those skills on his own.

In fact, intelligence may have nothing to do with it. Problems with

daily living skills "may be especially prominent in those with higher

cognitive abilities" and autism, according to one study.1

The Center for Excellence in Autism (CFEA)i s a leading provider

in the community offering services for individuals with an Autism

Spectrum Disorder (ASD). CLICK IMAGE TO GO TO SITE.

Autism and the College Experience

Marina Sarris

Interactive Autism Network at Kennedy Krieger Institute

ian@kennedykrieger.org

Date Published:

May 12, 2014

Elizabeth Cuff is a computer whiz and talented artist, but she decided

to leave college after just one semester. It wasn't the work that

stumped her, but rather decoding what professors wanted. Liz has

Asperger's Syndrome, and though she got some "accommodations" from the

college, "it was not what I was expecting," she said. "There wasn't

enough support, like I was used to in high school."

She had trouble asking teachers for help when they looked busy, and she

had to wait to get answers to questions. She found the instructions for

some assignments to be baffling.

Many U.S. students struggle to adjust to the challenges of college:

dormitory living, sudden independence, rigorous classes, and a new

social world. But for people with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD), the

transition can be more abrupt and dramatic.

The Individualized Education Programs (IEPs, for short) that helped them

from elementary through high school disappear in college.

Their parents are no

longer able, or welcome, to advocate for them. And their struggles with

communication, organization or interpreting social nuances can multiply

exponentially in college, away from the watchful eye and structured

world of parents, principals and special education teachers.

Researchers have found that young adults with ASD have low rates of

employment and education after they leave high school.

They were less likely

to be employed than youth with intellectual disability, a learning

disability, or a speech/language impairment. More than half of the youth

with ASD had no job and no school participation in the first two years

after high school, a higher percentage than the youth with those other

disabilities.1

The picture improves with time. Almost 35 percent attended college and

55 percent held a paying job in the first six years after receiving high

school diplomas or certificates.1 Still, most students with ASD either

don't apply to college, don't get admitted, or don't stay in college.2,3

Many people with autism are capable of a college degree but require a

range of supports to help them succeed.4 As Ms. Cuff found, however, the

supports available in most colleges differ radically from what's

available in high schools. And those college supports may not address

some of the unique needs of students on the spectrum.

To help prepare students for college, parents should gradually give them

more responsibility. For example, they shouldn't always rescue them when

they miss due dates or forget materials they need for school at home,

said an article in a publication for school psychologists. "Students

need self-knowledge in order to understand what kind of weaknesses they

will have to account for in the unstructured world of college," it

advised.5

Needed: An "Interpreter of the Social World" for Students with ASD

The biggest issue is not academics. It's navigating the social

environment and having the independent living skills necessary to be

away at college.

Colleges and universities are used to providing accommodations to

students with learning or physical disabilities, but students with ASD

often have needs that extend beyond the classroom, Dr. VanBergeijk said.

"If you send a person to college with a hearing impairment, you provide

an interpreter of the hearing world, but our people on the spectrum need

an interpreter of the social world," he explained. "The biggest issue is

not academics. It's navigating the social environment and having the

independent living skills necessary to be away at college."

A student may be accused of stalking because he doesn't know how to show

his interest in a potential date appropriately, he may irritate

professors by interrupting and correcting them, or he may become upset

if someone sits in "his spot," he said. The student may become a target.

He knew one student with ASD who left an Ivy League university because

of bullying in the dormitory, he said.

Students may need special accommodations for dorm living, such as the

option for a single room and lighting that doesn't cause sensory

problems. Whether colleges can provide that is "hit or miss," he said.

Colleges may interpret the U.S. Americans with Disabilities Act

differently and may be affected by their size, budget and mission, he

said.

Mr. Magro, 26, said he had a "disability single" – a single room for

students with a disability – as a freshman. He served as a resident

advisor in his sophomore and junior years, which afforded him his own

dorm room.

His freshman year was the hardest, as he moved from a tiny high school

to a much larger university. "It was a rough transition to learn how to

get along with other people and how to meet other people," he said. "One

of the big things that helped me was asking questions, and really

working on adjusting to college life by keeping in touch with family and

close friends from home," he said.

He also went public with his diagnosis. He gave a presentation on autism

in class, and at the end, he told his classmates he was on the spectrum,

diagnosed with Pervasive Developmental Disorder-Not Otherwise Specified

at age 4. "For the most part, people were warm and welcoming," said Mr.

Magro, now an Autism Speaks staffer, motivational speaker and author.

An article by Dr. VanBergeijk and researchers Ami Klin and Fred Volkmar

recommended that colleges offer social skills groups, counseling,

vocational training and life coaching to students with ASD. They also

encouraged students to take community college courses while still in

high school.4

|

AUTISM IN DATING, RELATIONSHIPS,

MARRIAGE, DIVORCE, FAMILY |

Introduction

The desire to connect with another person and build a satisfying

relationship exists in everyone. It is common and natural for people

with autism and other developmental disabilities to seek companionship;

however, they often experience problems due to difficulties

communicating with others and recognizing non-verbal cues.

For parents and other family members, their loved ones’ safety is a

common concern. It is important to keep in mind that with support,

people with disabilities are able to overcome challenges associated with

dating and develop successful relationships.

Dating

Dating allows two people

to get to know each other better; however, it can be a confusing process

to navigate.

If you are interested

in someone, how do you act on those feelings? How do you ask someone out

on a date? What steps should you take to prepare for a date?

Becoming Empowered

and Katherine McLaughlin.

Online dating has

become a popular and quick way to meet people. Unlike traditional

dating, meeting online gives each person the opportunity to protect

their identity until he/she feels comfortable enough to reveal more

personal details. This is especially helpful for individuals who prefer

to wait to disclose their disability. Although there are benefits to

online dating, taking the necessary safety precautions is important.

Romantic

Relationships

Common characteristics

of autism spectrum disorders (ASD) may make it difficult for individuals

to initiate and manage romantic relationships.

Discomfort with physical

affection, high levels of anxiety, and difficulty with eye contact may

lead to lack of affection and intimacy within the relationship.

Fortunately, these issues can be managed with open and honest

communication.

Individual with ASD should explain to their partners why they behave the

way that they do. Partners, in turn, should be supportive and willing to

compromise so that a comfortable median can be reached. Many people on

the autism spectrum are looking to be in a relationship; however, there

are others who are content with being single.

Dating and choosing to be

in a relationship are personal choices that depend on the needs and

preferences of the individual. Below are a few ways that parents and

caregivers can support their loved ones through this journey:

■Talk about

relationships and dating and let the individual decide whether it is for

them. If he/she wants to pursue dating, inform him/her about acceptable

behaviors, the importance of consent and personal space, and other

expectations.

■Encourage the

individual to get involved in group events and activities. Interacting

with peers may create more opportunities for finding a potential

partner. ■ Do

research. Reading books, exploring websites, and talking to other

parents, counselors and educators are useful ways to learn more about

how to effectively support individuals with disabilities in dating and

relationships.

Tips from

Self-Advocates

The following suggestions are written by people who identify themselves

as having a developmental disability. These people present their own

recommendations based upon their own experiences.

Moving From Friend

to Partner/Sweetheart

When I was in school it

was not easy to make friends. I started to get out in my community and

meet people at groups, volunteering, clubs and playing sports. And it is

a big challenge to find a friend.

You have to put

yourself out there to find the right friend. Friends don’t care if you

have a disability or not. Friends like you for who you are, not what you

give them. Imagine you are at a dance and out of nowhere there is

someone standing close to you.

Like a genie they keep

popping up, checking you out. Will you feel too shy to ask them to

dance?

You need to walk,

cruise over and introduce yourself and shake the person’s hand and tell

them your name.

Step 1: Feeling

Interested When you have a crush on someone you need to decide if you

are going to act on those feelings. Ask yourself: Can a potential

girlfriend/boyfriend be…. Someone already in a relationship? Someone who

has said she/he is not interested? A paid support person/teacher?

Someone under 16?

Step 2: Getting

to Know Someone After you meet that person you need to spend time with

them and see how they act around you. Use your self-advocacy skills and

let the person know how you feel by: Tell the person how you feel (“I

like you and I like spending time with you.”) Talking on the telephone.

Ask him/her to join you at a group activity. Ask him/her out on a date.

Step 3: Becoming

a Couple Relationships usually start off being fun and exciting. Here

are a few topics you may need to talk about as a couple. When conflicts

come up it’s often not the issue, but how you work through it and learn

how to communicate better.

Feelings about

commitment—Will you only date each other?

Feelings about touch—What

kind? How much?

Communication—How

will you communicate with each other (phone calls, e-mails, text

messages, etc.)?

How often?

How much time will you

spend together?

How often will you see

each other?

How to handle a long

distance relationship?

Resources:

Interactive Autism Network:

Romantic Relationships for Young Adults with Asperger’s Syndrome and

High-Functioning Autism

Dating, Marriage & Autism: A Personal Perspective

THE BOOK: The

Asperger Love Guide

The Asperger Love Guide: A Practical Guide for Adults with

Asperger's Syndrome to Seeking, Establishing and Maintaining Successful

Relationships (Lucky Duck Books) , Kindle Edition by Genevieve Edmonds

(Author), Dean Worton (Author) 4.0 out of 5 stars 1 customer review See

all 4 formats and editions Kindle Edition CDN$ 24.44 Read with Our Free

App Hardcover CDN$ 175.95 1 Used from CDN$ 284.40 8 New from CDN$ 107.48 |